Posted: Aug 28, 2018

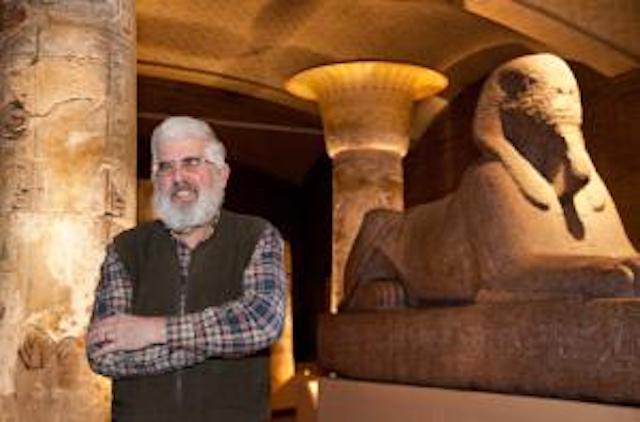

Entering his eighth decade upon Earth, his mouthful of a Wikipedia description has him as “the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology.” Best known for having written ‘Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture’ in 2003, his latest work is ‘Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages’ (UCBerkeley). He also consults on Dogfish Head Brewery’s ancient ale projects.

Entering his eighth decade upon Earth, his mouthful of a Wikipedia description has him as “the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology.” Best known for having written ‘Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture’ in 2003, his latest work is ‘Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages’ (UCBerkeley). He also consults on Dogfish Head Brewery’s ancient ale projects.

Some background on Patrick McGovern: how did you end up specializing in the rarified area of alcohol beverage archaeological research?

I was working in 1988 with a German chemist, Rudolph Michel, whose family had been wine merchants in the Pfalz area of Germany. I had picked grapes on the Mosel in 1971, the vintage of the century. Together, we analyzed a sample from Godin Tepe (Iran) dating to circa 3400 BC and found tartaric acid/tartrate (the biomarker of grape) and tree resin.

The latest posting on your University of Pennsylvania website speaks to findings confirming the efficacy of the anti-cancer effects of herbs added to alcohol beverages. Please explain.

When we started getting samples containing volatile compounds such as monoterpenes, we noted they were probably related to herbs and speculated that they could have been added to wines, leading us to wonder ‘why is it that herbs were being added to wines’? China, India, Egypt, Greece, Rome all have pharmacopoeial histories of adding herbs to drinks. I was invited to speak at COPIA in Napa years ago, and when I flew out I was in 1st Class seated next to a director of the U. of Penn Cancer Center. We got to talking, and decided to do a ‘Digging for Drug Discovery’ project, that’s when it started. The anti-cancer properties of the herbs, for example Artemisia argyi and A. annua in the wormwood/mugwort family, from a liquid rice beer sample from China, turned out to have extraordinary anti-cancer and anti-malarial effects, showing us that ancient humans were coming up with practical knowledge of herbs applied to medicinal use. Ancient humans had already been going through their environments sorting out which plants had medicinal effects, which might cure diseases and prolong life beyond the usual 20-30 years. We still have much to learn by using this approach to drug discovery.

How has the development of our contemporary US civilization been affected by that of wine?

By initially applying French viticultural and fermentation methods, we’re tapping into ancient methods that go back millennia. In a sense you’re taking archaeological developments from elsewhere and applying them here. The Georgian example of fermenting in clay vessels above or below ground shows that there is still a lot to be rediscovered and applied in the New World.

With Americans’ interest in heirloom varieties of fruits & vegetables, why do you reckon an attendant level of interest hasn’t carried over into what’s arguably a more ‘sophisticated’ sector--wine? That is, why hasn’t there been a scramble to plant more ancient, high quality grape varieties such as Saperavi or Falanghina?

There certainly has been an over-concentration on certain French and Italian varieties--and with some 7000 or more grape varieties in the world, there’s a lot more to explore. Wine producers, with vines already in place, and consumers who deal with a complex beverage, are focused upon varieties such as Pinot noir, which are known and admired. I think they’re in a rut in a way. I was working with Sean Thackrey who once was going to do a ‘retsina’ for which I had some pine resin sent to him from Mexico, but it turns out that he was one of many winemakers who didn’t go ahead with these sort of experiments. I never got anyone else to take me up on the challenge of producing an ancient style of resinated wine.

You’ve delved into some of the more eclectic, historically-based aspects of wine production via countries in east Asia, the Caucasus, and South America. How might recent discoveries garnered there effect modern production of wine?

The takeaway is that we should all be more open to ancient precedents such as clay vessels to make modern wine. The ceramic properties of clay are such that it’s more similar to cement with its ionic properties, which makes it hold different compounds in place and catalyze aromas and flavors, creating a different kind of wine. If you use clay from your particular area with a ‘terroir’ approach, it’s worth seeing what you can come up with. We have a lot more to find out about how the ancients made their wines, and it could be better than what we’re doing now. They were very attuned to their senses; why do we like Pinot noir so much? The monks knew that this grape acquired great qualities from these sites in Burgundy. It’s not all about scientific experimentation, but also using all your senses to create something special.

When planning a ‘dig’, what steps must be taken to ensure its success?

This can be very difficult because many winemaking facilities are located far away from the main settlements, and there haven’t been many excavations of winemaking facilities overall. You have to look for devices such as funnels to transfer liquids to lead you to sites. One of the best examples is Pompeii, which was encased in volcanic ash and pumice, and where you could see exactly where vines were planted and with facilities nearby where the wines were made, but because of carbonization you can’t do carbon testing to assess age or carry out DNA and other organic analyses to determine the ancient varieties. You should preferably use glass containers to collect the samples, to prevent plastic contamination. Wearing gloves, so as to prevent skin and lotion contamination, is de rigeur.

Of the many unusual alcohol beverages you’ve sampled, which stand out most to you for their hedonic impact and which for their academic rigor?

The technique of drying grapes before pressing that goes into an Amarone or one of the Muscats from the island of Pantelleria and elsewhere carries on an ancient tradition of true hedonism. It was drying grapes written of by Mago the Carthaginian, who is credited with the first textbook on viniculture (circa 3rd-2nd BC). He wrote of the multiple drying and pressing of the grapes in North Africa. The result: a delicious, almost ethereal sweet wine that was considered one of the epitomes of ancient winemaking. When you drink one of those today, it’s as though you’re drinking one of the finest wines from antiquity. You can even age these, and others such as the 1971 vintage I worked on at Trittenheim on the Mosel, though those were botrytis-dried, and find other great characteristics. I’m a great fan of wines made from dried grapes. Academically, Ridge’s Monte Bello, whose winery was originally set up with Stanford University’s involvement, sets the standard. Headed by Paul Draper, these tasters who’ve been doing this for 25 years or more are keenly aware of the vineyard’s character. They try to bring their senses to the fore in producing the best wine they can from a special location. It’s a good example of how art and science can be combined.

What’s got you curious now--what’s left undiscovered? We’re still working on the Georgian and eastern Turkey wines in nailing down just how early wine was made there, and now have better samples to analyze in our new project going back to 6000-7000 BC when pottery first began in the Middle East.

And just how did that 3000 yr. old millet wine taste, which is pictured on your homepage?! I could not taste it--that’d be destroying the evidence! I was smelling it, and in doing so possibly destroying some olfactory compounds. The smell of it was almost like an aged Sherry, a lot of volatiles coming off of it, telling us that it was something worth analyzing. In the old days scientists actually would taste wines--we don’t taste them these days but we do smell them.

By David Furer

January 8, 2015

Source: San Francisco Wine School

Please contact David Here

Go-Wine's mission is to organize food and beverage information and make it universally accessible and beneficial. These are the benefits of sharing your article in Go-Wine.com

The Wine Thief Bistro & Specialty Wines is a locally owned small business in downtown Frankfort, IL offering world class wines in a relaxed, casual gathering spot for friends and family. Offering world class virtual tastings and touchless carryout.

https://www.twtwineclub.com/aboutus

Go-Wine 25 Great Wineries in US selection prioritizes quality, value and availability.

www.go-wine.com/great-wineries-in-america

Tasting wine is a nice experience, but visiting the places in which wine is made is a magic moment. Available in New York City for touchless pickup.